The

Old Bed

This undressing on the grave,

this is what I would call looking into the future. When she stepped on

the tombstone, her heavy white body looked stupid like in the surgery.

Wait! I looked around. She was turning and stoop-ing on the stone, its

polished surface reflec-ted her heaving breasts. I placed her clothes

behind me, out of the picture. Jeba was lying on the black table; I was

surrendering to her! Is it going be accepted? And she – is she going to

accept my sacrifice? I looked around. Though his presence was gone, his

joyful whisperings encouraged us. She was lying prone, her flesh was sagging

down. Her figure was becoming flattish: her breasts, hips, legs were loosing

their bed-like shape.

|

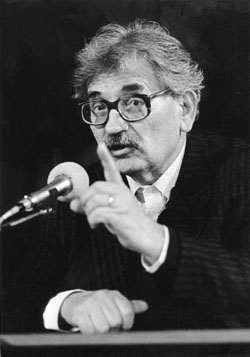

For several decades, Ludvík Vaculík

has been providing a brilliant and thought-provoking commentary on Czech

cultural and political life in his weekly feuilletons. His novels The

Axe (1966), The Guinea Pigs (1970) and A Cup of Coffee with

My Interrogator established his international reputation as a major novelist

of his generation. At the beginning of the eighties, he published a diary

novel The Czech Dreambook, which recorded the real and imaginary

events of 1979. In his novel How to make a boy, also written in

the form of the diary entries, he moves away from public and political

con-cerns into the more difficult territory of modern relationships. His

latest novel Immemoirs appeared this year.

Ludvík Vaculík již několik desetiletí ve svých fejetonech

přemýšlivě a pronikavě komentuje český kulturní a politický život. Jeho

romány Sekyra (1966) a Morčata (1970) mu získaly mezinárodní

uznání spisovatele své generace. V anglicky mluvícím světě jsou známy vybrané

eseje pod názvem A Cup of Coffee with My Interrogator. Na začátku

osmdesátých let vyšel jeho románový deník Český snář, zaznamenávající

skutečné i imaginární události roku 1979, po něm následuje vzpomínkový

soubor Moji milí spolužáci. V románu Jak se dělá chlapec,

rovněž ve formě deníkových záznamů, opouští věci politické a veřejné, vydává

se do složitého světa lidských vztahů. Jeho zatím posledním románem jsou

Nepaměti (1998). |

How

to Make a Boy

You may remember, dear Dominik,

the last time you were in hospital most women came to say goodbye, but

one came to greet you. A strange young woman sat on the edge of your bed

saying nothing, just looking at you. When you saw her, you closed your

eyes, when you opened them again, she was still there, and then you believed

in her. A woman with a pale face framed with dark hair, a face which dissolved

into a loving purity despite its austere features, a purity prepared to

sacrifice itself to your love. But it was already late, you could only

look at her. She didn’t speak, just as she doesn’t speak to me, and you

– what was there to say and why? When you could no longer weigh her down

with your light body. And so you simply took a strand of her hair, she

told me, and twice pulled it tenderly, a little clumsily, but still with

all your strength. I have come to see you, she said with her silence.

I’ll be with you. But that

was something you knew, it was understood. And she would have been with

you right there on the bed, had you only given her the slightest sign.

But if I were to believe her, and I find it difficult, you did not place

your hand on her knee, did not caress her thigh, did not stroke your way

up into her box with two, three bony fingers. And so you, a Carpathian

shepherd, failed for the first time in your main role, because you did

not lie with a woman who had brought her pleasure box for that purpose,

having listened to your name, your poetry and her own ambition to be one

of your most beloved. Then, said Naja, you spoke my name. Why? I would

have liked to ask the woman, but I didn’t since she had not and still continues

not speak to me; are we on unspeaking terms?

We went out into the countryside

twice and each time she would not even answer my questions about where

we were going and why, where she wanted to go and why. The meadow was damp,

and when I finally asked her directly what it was she wanted from me, she

never answered. Today is my sixty-fourth birthday. I knew fewer women than

you, but then I often intentionally ignored them, having had strict morals

for a long time. I still do, when I think about it. That’s why I am looking

for a proper excuse, at least, and I reach for simple words of thanks with

difficulty. I fear them, mostly. Women. And because I am inca-pable of

letting things go, I make a nuisance of myself, I become ridiculous. I

am looking for content and meaning. Why do you want to be with me if you

don’t speak a word? But Naja is not willing or perhaps not able to talk

about anything, discuss anything, vent her views, feelings and impressions.

That is, Dominik, a difficult situation for a man who neither wants to

nor will become an entertainer, an attraction or an all-knowing sage for

a woman. And yet, there were numerous communications of physical intimacy,

that woman, your lover, had perhaps realized that she could not consistently

drive away my hands, my mouth from her breasts and from that bush as black

as her head; but still no opinion, no wish – which I didn’t mind, Dominik,

as long as I had a notion of what she wanted. But we Carpathian shepherds

are proud of our standing with women, we expect to hear each one declare

why we have been privileged to be included into her belly. Because we are

not happy to admit that we are there in place of someone else, and that

we are simply part of a lunar play. I know from all your reports that you

have always received such declarations of unique purpose from women, and

then wrote them down, wrote down their saying you were their most beloved.

Those lies.

She never speaks to me about

her work or about mine, until today I don’t know what we have in common,

except that we agree about our differences. And I am forty years older

than when I first ventured with my shepherd’s staff into the chasms under

the Mare, and some-times I wonder, watching myself from above with a smile.

Then there are the nights: to prize her box open with my tool through the

vortex of hair is nearly impossible, since she herself does not yet know

how to touch the so-called male organ with her virginal hand. The last

time I said to myself: This is the last time! Because the situation threatened

with a child.

I have never seen a child

in her. Her beautiful sighs floated past my head, ignoring it. I tried

to hold on to them, looking for something for myself, but I had to realize,

gladly and with a delightful sadness that I was nothing more than a flint

stone which lights up her pleasure, the pleasure of her own body, hers

alone, which he seeks freely – and who does she love? She loves herself

so much that for her own sake she is willing to sacrifice herself to a

man. She had enough patience with me, but it was passive patience. Dominik,

you’d have to talk a lot to her, but there would be no compulsion on your

part, because you like to talk freely and voluntarily. I don’t! She is

like some fragile apple variety: in the morning she is covered with bruises

from ankles up to her hips and on all over her inner thighs. Until now

I had considered myself to be quite tender, but she said she was used to

men who were even more tender than me. I did, of course, think of you,

and marveled at the game fate plays with us: how come I am now on top of

her? Her body is very lovely: firm, elongated, a narrow stem above jug-shaped

hips... or rather like a fine, drawn glass vase. And although her contours

are light and gentle, she is a heavy sight. The magnificent heavy loaves

of her behind told me more than her head, or rather her behind and her

belly corrected the untruthful dispatches from elsewhere. She lights up

at the first touch and has a rapid running: she runs, twists and turns,

clings and clutches, her soul has firm, elastic walls, tactile. The head

seems to know nothing about itself, falling away, thrashing with its hair,

and once, moaning with love, love for herself, which she invited me to

witness and the invitation pleased me in a way she will understand in twenty

years, as I lived her, with awe and rever-ence and perhaps even with love,

she spoke. Intoxicated, writhing, she suddenly said, sighed: “Dominik!”

I passed it, smooth-sanded it and glossed it over, I understood it and

accepted it with a sense of reconciliation, sadness and joy, but then she

really didn’t know about it. I realized however that I couldn’t keep it

away from you. Each and every one of us means something to another person,

and often it is something else than what we know.

This sixth time was

as if I had at last fulfilled my word and my purpose. She leaned over me

in the twilight with her breasts, shoulders and face, caressing and kissing

me. She be-came a lover. When I regained some strength, and I could sit

up opposite her and look at her, she regained some sense and said: I don’t

want to fall in love.

translated

by Alexandra Büchler

|